- Description of the Palaung Location

- Brief History of the Palaung People

- The Palaung People in Burma

- The Palaung People in China

- The Palaung People in Thailand

- The Palaung Hill Tribe in Chiang Mai

- Tea Production On the Periphery of the British Empire

- Background of The Palaung people in Thailand

- The Palaung People in Kalaw Village in Northern Shan State

- Palaung People in Moegoke

Description of the Palaung Location

The various Palaung groups of Myanmar live in Shan State. Some are located in the northwestern corner around Tawngpeng, while others live as far south as Kengteng. It is thought that the Palaung immigrated to Myanmar before the Shan, who came from China during the twelfth century. The Palaung cluster consists of several smaller groups including the Rumai Palaung, the Riang-Lang, the Golden Palaung (or Shwe), and the Silver Palaung, each of which speaks its own language. Some groups are bilingual, speaking their native dialects at home, and either Burmese or Shan while in official, literary, or religious circles.

Myanmar, or Burma, has a long history of coups, wars, and rebellions. Ethnic divisions and political unrest have been common since the first Burman kingdom in the eleventh century. Today, the Burmese military maintains forcible control over the ethnic groups, such as the Palaung, who want equal importance in the government and in commerce. In May of 1994, over 17 battles occurred in Shan State. The Palaung often find themselves innocently, but forcibly, involved in much of the conflict.

What Are Their Lives Like?

Shan State consists of mountain ridges separated by narrow valleys. There is some open grassland, but most of the area is uncultivated forest land. The Palaung are traditionally farmers. They raise rice, grains, and vegetables by using the “slash and burn” method. Tea is also grown as a commercial crop. Those living in the hills, such as the Rumai, cultivate little besides tea and are not able to grow enough rice for themselves. In former times, they used pack bulls to transport the tea to other regions for trade. Today, they have a monopoly on “pickled tea,” which they trade for items such as rice, salt, and dried fish.

Groups living at lower elevations, such as the Silver Palaung, grow more rice than tea. There are some terraced, irrigated rice fields in this area; however, most of the farmers still use the rotation method of cultivation.

The Palaung live in villages together with other ethnic tribes, such as the Shan or the Burmese. Over the years, the Palaung have steadily assimilated through intermarriage. Since there are no Palaung traditions forbidding inter-tribal marriages, Palaung-Shan marriages are particularly common. This explains why the Shan have had the greatest amount of cultural influence over them. Among the Palaung, extended families live together in oval-shaped, bamboo houses that are raised on posts about six feet above the ground. Some are up to 100 feet in length and contain numerous families. Their diet is predominantly vegetarian.

Palaung social culture is a hierarchy based on age, gender, and wealth. The Myanmar constitution dictates the political organization-an unbroken line of administrative authority from the Prime Minister to the village headman. The community, which elects a single headman, is accounted for in the national census as a territorial unit and accessed taxes. For the common Palaung citizen, the government is one of five traditional enemies along with fire, famine, flood, and plague.

What are their beliefs?

Buddhism was introduced into Myanmar in the fifth century; and today, most of the Palaung are Buddhists. However, they have also maintained their ethnic animist religion, which is a primitive system of beliefs based on evil spirits called nats. The Palaung believe that while all of the nats are inherently evil, some are more evil than others. One must spend their life trying to appease the nats. If the nats are pleased the people will have a bountiful harvest and good health. If favor is not found with the nats, the people may be subject to great harm. The Palaung believe that these spirits can do almost anything in nature, such as prevent floods and other natural disasters.

What are their needs?

The Palaung have been tremendously affected by the fighting and bloodshed of the past. They need healing and new spiritual hope. There is a great need for Christian radio and television broadcasts as well as Christian literature to be made available in their native languages. They also need translations of the Bible in their various dialects, since only the Riang-Lang have portions of scripture in their language.

Prayer Points

Take authority over the spiritual principalities and powers that are keeping the Palaung bound. Ask God to call out prayer teams who will begin breaking up the soil through worship and intercession. Pray that the Lord of the harvest will send many laborers into Myanmar to share Christ with the Palaung. Ask God to protect and encourage the small number of Palaung believers. Pray that the Palaung Christians will be a clear witness to their people of God’s goodness and grace. Ask the Holy Spirit to soften the hearts of the Palaung towards the Gospel.

Pray for God to rise up linguists to translate the Bible into the remaining Palaung languages. Ask God to create a hunger within the hearts of the Palaung to know the Truth. Pray for a strong church to be raised up among the Palaung. Text source: Bethany World Prayer Center © 1999. Used with permission from Adopt-A-People Clearinghouse View Palaung, Rumai in all countries.

http://www.joshuaproject.net/peopctry.php?rog3=BM&rop3=108436

Brief History of the Palaung People

The Palaung people are one of the indigenous nationalities within the multi-national in the Union of Burma. The Palaung are descended from Mon-Khmer from Mongolia passing China to Burma. The Palaung people have a long history and a strong sense of their unique identity. They have their own language and literature, a distinctive traditional culture, their own territory and a self-sufficient economy. The Palaung are predominantly Buddhist with less then ten percent animist and Christians.

The Palaung population is over one million, and most lives in the mountains of the northwestern Shan State. But large numbers also live in towns throughout the Southern and Eastern Shan State. The customary lands of the Palaung people have lots of ruby and sapphire mines in the region, including the famous Moegok mine area, which has been cut out of Shan State and made a part of Mandalay Division by the Burmese dictatorship. There are also many kinds of minerals in the Palaung lands including silver, zinc, gold and aluminum. The Palaung tea is famous in Burma for the high quality that is grown in their upland farms. They also grow a variety of temperate climate fruit crops such as apples, plums, avocados and pears, which are highly valued in the lowland areas. Unfortunately, the Palaung people have not been able to live peacefully and tend their lands. For centuries they have suffered offensive of their territories by Burmese army and other armies. First, the Burmese kings tried to expand their imperial reach into Palaung lands and then became the British colonialists. The Japanese imperialists in turn followed them, shortly after World War II. The Chinese nationalist Kuomintang moved into the lands of the Palaung where the Burmese army fought them.

The Burmese army declared a coup d’etat and established the Burma Socialist Programmed Party (BSPP) in 1962. After that the Burmese army committed many injustices against the people, and the Palaung people along with many other nationalities, took up arms against them. Then the BSPP regime encouraged gun running armed groups in the Shan State to become Ka Kwe Ye (people’s militia) to fight for the government against the indigenous nationalities armies. At that year, General Ne Win took power over Burma. After this, the Burman army committed many injustices against the people, and the Palaung people, along with many other ethnic nationalities, took up arms against them. In 1988 the Burmese government was reorganized and a dictatorship was formed called the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). SLORC put pressure on the Palaung people to force the Palaung State Liberation Army (PSLA) to negotiate with them. First, they cut off communications between the PSLA and the Palaung villagers. They forcibly relocated villagers to sites near towns during the tea-harvesting season. As a result, the villagers could not their harvest tea, and they suffered great difficulties from the loss of income. The PSLA feared the situation might worsen, so they were forced to negotiate with SLORC to provide relief to the Palaung people. They reached a cease-fire agreement in 1991. Even with the cease-fire agreement, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) continue to commit human rights abuses in Palaung land. Many Palaung have become “internal refugees” trying to survive in remote areas in the hills. Some fled to take refuge at the China border and in the northern border areas of Thailand. In 1968 the Burma Communist Party (BCP), backed by the Chinese communists and also established bases in Palaung lands and fought against the Burmese. In 1988 the dictatorship was formed and called itself the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). One year later, the BCP collapsed from internal problems and spilt into different ethnic armies. Some of these immediately made cease-fires with the SLORC. In Shan State the independent non-communist indigenous armies opposed the dictatorship, but they faced confrontation of the SPDC troops.

The people who facing the threat of total destruction are the Pa-O army, some Kachin units based in the Shan State and some Shan armed forces made deals with the SLORC. The Palaung State Liberation Army (PSLA) was left surrounded by a very large number of SLORC troops and had no choice so they had to sign a cease-fire agreement as well. The Chinese-Shan warlord Khun Sa Loa Maw expanded his soldiers throughout the Shan State and forced many young Palaung joining his army that was attacked by the Burmese and sometimes also Wa cease-fire group. Because of the long years of fighting, some Palaung villagers fled to more peaceful areas. Many become ” internal refugees ” trying to survive in isolated areas in the hills of Shan State. Some, due to the brutal oppression of the Burmese armed forces and sometimes drug trafficking groups, fled to take refuge in the northern Thai border areas. Some refugee settlements have been set up in Thailand for nearly 18 years. Since opium king pin Khun Sa’s surrendered on 1st January 1996 to the SLORC, many other Palaung villagers who had lived in areas under Khun Sa’s control and whose family members had been forced joining his army have also fled to Thailand. Now there are about 5,000 Palaung refugees in the north of Thailand.

The Palaung People in Burma

The Palaung have a 40-year history of armed resistance through the Palaung State Liberation Army – the military wing of their political liberation organization. Even though a cease-fire has been in effect for the past 12 years, the Palaung State Liberation Front has been associated with other ethnic minority-led armed resistance movements in Thailand. They are currently trying to secure three-way peace talks between Myanmar’s military rulers, the pan ethnic armed resistance movements and the (currently interned) national pro-democracy leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. The Palaung people live in mountainous areas because they can grow the tae in the mountains that make them for survival. They are famous for the high quality tea they grow there. Palaung tea is famous in Burma. The Palaung is one of the indigenous ethnics in Burma. Mostly they are living in Northern Shan State and some are in the South. Palaung people, they call themselves “Ta-ang” as the Palaung language. In Burmese or else, they are called “Palaung”.

They are about over one million populations living in Burma (estimated). They live in different place. The Palaung are descended from Mon-Khmer from Mongolia passing China to Burma. The Palaung people have along history and a strong sense of their unique identities. They have their own language and literature, a distinctive traditional culture, their own territory and self-sufficient economy. Most Palaung work in agriculture, farming, tea planting and logging work. Many communities make most of their income from the growing of tea in their villages, which are usually located on steep hillsides amongst evergreen forests. They also grow once a year paddy in their farms. Most of them are farmers. Most of Palaung people are Buddhists. Most of their villages have a temple, and the monks who live there depend on the offerings of the followers to provide for their daily needs. The villagers, in turn, depend on the monks for spiritual guidance. Each village also looks to layman who directs the offering-making ceremonies and practices divination. Buddhists, they believe one thing that if you do the right thing, you’ll get the right thing and if you do the wrong thing, you’ll get the wrong thing. Like all Buddhists, the Palaung believe they should try to do good works, to gain merit for their next life. They believe that fate predetermines the events in their lives. This results in them having little concern to change their ways, and long-deadened consciences in regard to sin.

Their Buddhist practices are also mixed with animistic beliefs. Animists believe in the spirit-realm, and are careful not to upset them in case the vengeful demons extract retribution on them. Shamans – or witch doctors – are powerful figures in Palaung society. The shamans are the link between the community and the spirit-world. No important event like a wedding, funeral, or long journey is undertaken without first consulting the local shaman, who enters into a trance and announces whether or not the event should happen, and when is the most auspicious date and time. There are some Palaung people in Northern Thailand about 5000. The Palaung are the most recent ethnic group to arrive in Thailand. They have come here from neighboring Myanmar (Burma), where they are one of that country’s most ancient indigenous peoples. They have fled in the past 20 years from Shan State and Kachin State to escape persecution and oppression at the hands of Myanmar’s military rulers. Many of the Palaung in Thailand are refugees living in refugee camps. There are also Palaung people in Southern China about 15, 500. The Palaung live scattered across the Yunnan Province of southwestern China.

The Palaung are the smallest registered minority in China, due largely to a high infant mortality rate. Fortunately, China’s medical care has greatly improved since the 1950′s, and their population growth rate has seen a steady increase. Most of the Palaung live in mountainous areas that are also inhabited by the Lisu, and Wa peoples. A small number of Palaung also live in flatland villages among the Dai. Because they generally share villages with other minority groups, most of the Palaung are bilingual. Although most of the Palaung are farmers or lumberjacks, many earn their incomes by growing and selling opium.

The Palaung People in China

The Palaung, also known as the Ta-ang, live scattered across the Yunnan Province of southwestern China. The Palaung are the smallest registered minority in China, due largely to a high infant mortality rate. Fortunately, China’s medical care has greatly improved since the 1950′s, and their population growth rate has seen a steady increase. Most of the Palaung live in mountainous areas that are also inhabited by the Jingpo, Han, Lisu, and Va peoples. A small number of Palaung also live in flatland villages among the Dai. Because they generally share villages with other minority groups, most of the Palaung are bilingual. Their native language is called Palaung.

Although most of the Palaung are farmers or lumberjacks, many earn their incomes by growing and selling opium. What are their lives like? Though the Palaung resemble the Dai in many aspects, they are easily identifiable when wearing their traditional costumes. The women keep their haircut short and wrap their heads in black turbans. They also wear heavy earrings and silver necklaces. The men are fond of tattoos. The Palaung usually settle in isolated farming villages that consist of a few dozen households.

Their chief crops are grain and tea. In addition to farming, they also engage in the production of various handicrafts such as bamboo weaving, making gunnysacks, and fashioning silverware. With profits earned by selling such items, the Palaung are able to buy metal tools, salt, cloth, and other manufactured goods at neighboring Dai or Han markets. Among the Palaung, everyone’s primary work is directly related to agriculture. Tasks are divided by age and sex. The men perform heavy work in the fields such as plowing, while the women are responsible for transplanting rice seedlings. The elderly engage in weaving and taking care of household chores. Traditionally, all land was the property of the entire Palaung village. Each family had the right to use the land, but not to own it. In the late 19th century, the economic forces of the Dai and Han peoples gradually began infiltrating the Palaung villages. By 1956, they had occupied 80-90% of the rice fields by buying the land from Palaung landowners. Losing the fields, many Palaung were reduced to being tenants of the Dai and Han landowners. What are their beliefs? The Palaung are 99.9% Hinayana Buddhists. Most of their villages have a temple, and the monks who live there depend on the offerings of the followers to provide for their daily needs. The villagers, in turn, depend on the monks for spiritual guidance. Each village also looks to one layman who directs the offering-making ceremonies and practices divination. Like all Buddhists, the Palaung believe that they should try to do good works in order to gain merit for their next life. Since they believe that fate predetermines the events of their lives, they have little concern for changing their ways.

Their consciences have long been deadened in regard to sin. Although the Palaung consider they to be Buddhists, their practices are heavily mixed with animism, (the belief that non-human objects have spirits). Shamans, or witch doctors, are powerful figures in the Palaung society. In funeral rites, monks chant for the dead. They believe that this will release the soul of the dead from purgatory, so that the ghost will not harm the people or the livestock. What are their needs? A majority of the Palaung has never heard the name of Jesus Christ. The Bible has not yet been translated into Palaung, and there are currently no mission’s agencies working amongst him or her. Trapped in bondage to demons, the Palaung have no hope without Jesus. Prayer Points —Take authority over the spiritual principalities and powers that are keeping the Palaung bound. —Ask the Lord to call people who are willing to go to China and share Christ with the Palaung. —Pray that the doors of China will soon open to missionaries. —Ask God to protect and encourage the small number of Palaung believers. —Pray that the Palaung Christians will be a clear witness to their people of God’s goodness and grace. —Ask the Holy Spirit to soften the hearts of the Palaung so that they will be convicted of their sins. —Pray for God to rise up qualified linguists to translate the Bible into Palaung. —Ask God to create a hunger within the hearts of the Palaung to know the Truth —Pray for a strong church to be raised up among the Palaung by the year 2000. The People People name: Palaung Country: China Their language: Palaung Population: (1990) 15,400 (1995) 16,300 (2000) 17,200 Largest religions: Buddhists (Therevada) (99%) Christians: 1% Church members: 163 Scriptures in their own language: None Jesus Film in their own language: None Christian broadcasts in their own language: None Mission agencies working among this people: None Persons who have heard the Gospel: 3,300 ` (20%) Those evangelized by local Christians: 1,100 (7%) Those evangelized from the outside: 2,200 (13%) Persons who have never heard the Gospel: 13,000 (80%) China Country: China Population: (1990) 1,135,043,400 (1995) 1,199,901,200 (2000) 1,262,195,800 Major peoples in size order: Han Chinese (Mandarin) 67.7% Han Chinese (Wu) 7.5% Han Chinese (Cantonese) 4.5% Major religions: Nonreligious 55% Chinese folk-religionists 17% Atheists 12.7% Number of denominations: 42 Source: www.bethany.com Note: Statistics from the latest estimates from the World Evangelization Research Center.

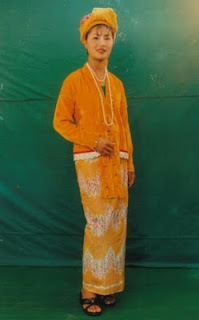

The Palaung People in Thailand

The Palaung are the most recent ethnic group to arrive in Thailand. They have come here from neighboring Myanmar (Burma), where they are one of that country’s most ancient indigenous peoples. They have fled in the past 20 years from Shan State and Kachin State to escape persecution and oppression at the hands of Myanmar’s military rulers. Many of the Palaung in Thailand are refugees living in refugee camps. There are three main sub-groups of the Palaung: Pale, Shwe and Rumai. Each of these sub-groups has their own language. Most of the Palaung who settled in northern Thailand are of the Pale, also known as Silver Palaung. The photographs here are of this sub-group.

Their women are very distinct in their dress. This includes a bright red skirt, worn like a sarong. Typically in the past, these “tube skirts” were made from cotton, which the Pale grew and dyed themselves, and were hand woven. Nowadays the cloth is more commonly bought in markets and hand weaving is giving way to machines. Around their waist are worn quite heavy silver hoops. These are said to symbolize an animal trap, set by the Lisu people, which accidentally ensnared Roi Ngoen, a visiting angel from whom they believe they are descended. The hoops are also believed to afford protection to the women. The Palaung traditionally have practiced a mixture of Animism and Buddhism. (Although there has been a small amount of recent Christian missionary work among them.) Whereas many associate Buddhism with a pacifistic lifestyle, the Palaung in Myanmar have a 40-year history of armed resistance through the Palaung State Liberation Army – the military wing of their political liberation organization. Even though a cease-fire has been in effect for the past 12 years, the Palaung State Liberation Front has been associated with other ethnic minority-led armed resistance movements in Myanmar.

They are currently trying to secure three-way peace talks between Myanmar’s military rulers, the pan ethnic armed resistance movements and the (currently interned) national pro-democracy leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. Like many others in Myanmar and Thailand who are nominally Buddhist, the Palaung also still practice various forms of Animist ritual from their religious past. The most famous such ritual is known as “nat worship.” Nats are believed to be the spirits of otherwise inanimate objects such as rocks, mountains and rivers, as well as the spirits of deceased ancestors. There are traditionally 37 different nats, to whom offerings of, for example, betel and tobacco are made on various ceremonial occasions – or simply to appease these spirits if someone falls sick or if a crop harvest has been bad. “Nat wives” are women who have “married” such a spirit, and are sometimes transvestite and/or homosexual men (see the documentary link below).

Palaung shamans, who are both respected and powerful in their communities, perform offerings to nats and other Animist rituals at events such as weddings, births and funerals. In 19th Century Myanmar, under British colonial rule, the Palaung were far more powerful in terms of land ownership and political representation than they are today. The British even recognized the Palaung-controlled kingdom of Tawnpeng. Today land ownership is being taken away from the Palaung by Myanmar’s military government. In Thailand many Palaung work as hired laborers on Thai-owned farms. To the extent that they continue to own land, they farm a variety of crops including tea, grain, rice, opium poppy, betel and corn. The photographs left and right show the Palaung harvesting corn and carrying it back to their village. While corn is a recent introduction to the crops of the Palaung, others such as rice, tea and opium poppy are generations old. Historically, and extending to the present day, opium poppy has been a lucrative cash crop to the Palaung. In Thailand government control and the efforts of non-governmental organizations have, for the most part, persuaded them to cultivate alternate cash crops such as coffee and beans. Efforts along these same lines in Myanmar lag behind those in Thailand, but are now underway. Nonetheless, peoples like the Palaung live in poverty relative to their immediate neighbors and due to the power of local drug-lords, as well as the corruption of law enforcers, it will be a long time, if ever, before they abandon opium poppy cultivation. (A recent news link is given below with some reporting and opinion on this issue as it relates to the cultivation of opium poppy among ethnic groups in Myanmar. The visitor to the border areas of northern Thailand can expect to be spot searched for drugs by Thai authorities.) Besides alternate cash crops, the Palaung have recently begun selling handicrafts to tourists to supplement their income. This is especially prevalent in northern Thailand, where many tour operators and guides take trekkers into Palaung villages. This type of tourism takes place to a lesser degree in Myanmar also. They sell, among other things, shoulder bags, wallets, hand-woven cloth and hand-made clothes. The visitor can overnight in some of these villages, which have basic yet comfortable wooden guest huts that have been purpose-built to accommodate tourists. The visitor might be surprised by how well these guest huts are built.

The Palaung are highly skilled in construction. Their own houses are also wooden huts, which are raised high off the ground on stilts. These days their houses are typically much smaller than in the past. Traditionally their houses have been longhouses accommodating extended families of 50 or more! While the typical house is home to fewer family members these days, the Palaung continue their tradition in which parents host their married sons and their daughters-in-law. Every Palaung village has a headman, whose duties involve making decisions for the village and ruling in disputes. The headman usually comes from the largest family in the village. In the village shown above right and left, Palaung men are building a new house for a husband and wife who are about to give birth to their first baby. Village men of all ages play some role in the construction, which symbolizes the wishes and blessing of the whole community.

Since the Palaung still use working elephants, the mahoot (elephant trainer) also employs the village elephant to sack and transport timber for the construction of the house. Books Howard, M. C. and Wattanapun, W., (2001) The Palaung in Northern Thailand. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. Diran, R. K.,(1997) The Vanishing Tribes of Burma. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Naing, U. M., (2000) National Ethnic Groups of Myanmar. (Trans. H. Thant) Yangon: Swiftwinds Books. Milne, L., (1924) and Home of an Eastern Clan: A Study of the Palaung of the Shan States. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. Source: www.peoplesoftheworld.org

The Palaung Hill Tribe in Chiang Mai

The Palaung are the newest hill tribe to arrive in Chiang Mai. Like the Lua they may have originally been lowland peoples. Both Lua and Palaung speak a language related to the Mon-Khmer family of languages. The Palaung have been living in the Shan State of Burma for several centuries but have only started moving into Thailand since 1984 to escape from the fighting in their homeland. They number more than 2000 and live in six villages in the Doi Ang Khang and Chiang Dao areas.

The Palaung are noted for their skill in raising crops. They are strict Buddhists who also believe in nature and animal spirits. Their villages must have a Buddhist temple or shrine as well as a shrine for propitiating the spirits. Living in raised houses, families are extended with married sons usually living with the parents. Villages have a headman, who usually comes from the largest family, as well as monks and a shaman for curing sickness. Only Palaung women wear costume. They wear a short bright (often blue) long sleeved jacket with decorated trim and a red tube skirt with narrow horizontal white stripes. The women also wear large belts made of rattan coils, which protect them and let them go to heaven when they die. Both women and men like to have silver and gold in their teeth. Source: www.chaingmail.com

Tea Production On the Periphery of the British Empire

Robert Maule Department of History, University of Toronto Many years prior to the incorporation of Burma into the British Empire, tea production had been an important economic activity in the non-Burman region. One source suggests that the necessity for Theravada Buddhist monks to observe the vineyard in a manner stricter than hitherto practiced stimulated tea production in some of the Shan States in the fourteenth century. [1] Local legend from one of the States, Tawngpeng,

[2] Indicates that tea seeds were obtained from a magical bird and brought to the region by King Alaungsithu of Pagan (1111-1167)

[3] Who gave the seeds to two Taungthu?

[4] Cultivators, the King ordered that the seeds be planted to the northwest of a local pagoda and that a festival be held annually to commemorate the event. After determining that the Palaung, the majority population in Tawngpeng, originated from a union between a Naga princess and the Sun King, he appointed Bala Kyautha Sao Hkun to head the local administration. [5]. Since the Taungthu recipients of the tea seeds accepted the King’s gift with one hand instead of with two, they were deemed to be uncivilized. Consequently, the tea plants were named let-pet (one-hand). Tawngpeng State, the major tea-producing area in the Federated Shan States,

[6] Contained an area of 938 square miles. As of 1939 the population of Tawngpeng was 59,398 and it had revenue of Rs. 645,634.

[7] The State was divided into 16 circles, which corresponded as closely as possible to clan-divisions. Geographic features were characterized by hills ranging from five to seven thousand feet in height interspersed with valleys that averaged approximately ten miles in length and from a few hundred yards to a few miles in width. Maurice Collis, a former Burma civil servant, noted that upon approaching Namhsan, the capital of Tawngpeng which lies at the centre of the State at a height of six thousand feet, ‘there is a vale and in the midst, ten miles away, is a ridge, on one end of which stands the town of Namhsan with the palace over it on a circular hill…. The vale is one vast tea garden’.

[8] On the lower levels of the hillsides, Palaung and Shan grow tea whilst higher up Kachin and Lisu practice shifting agriculture. Shan predominate in the valleys where rice is the staple crop. A survey conducted in 1896-97 by Mr. W.G. Wooster revealed that the State had 9,199 acres under cultivation of which 5,315 acres were taken up by tea production.

[9] Four crops were picked throughout the year: Shwepyi (May to July), Hka-gyin (July and August), Hka-rawt (Sept. and Oct.), and Kha-reng (Nov.). Both wet (salad or pickled) tea.

[10] And dry tea

[11] Were manufactured with four more times pickled tea than dry tea being produced? To obtain pickled tea, the picked tealeaves are laid out in the sun to dry for a few days before being steamed. After steaming, the leaves are compressed and placed into pits, which are weighted down. At this point the tealeaves are left to ferment until the desired result has been produced. Although there is no set time period for the fermentation process, the leaves are examined from time to time. The process for producing dry tea is far simpler. The picked leaves are placed on bamboo mats and left to dry in the sun.

[12] The majority of the tea gardens was located on hillsides and planted at random. Seed is collected in November and sown in nurseries in February or later. Once the plant reaches 2 feet in height, it is planted on cleared slopes in August and September. The trees are not pruned since the Palaung believe that pruning will cause the trees to die; consequently, they grow freely. Any available space in a garden is filled annually with new trees. The plants are picked for the first time in the fourth year, and they continue to bear useable leaves for a period of ten to twelve years.

[13] At the end of its lifespan, the garden is often cut down and burnt. In the late-nineteenth century, the tea gardens were considered to be the common property of the village. Capital-intensive plantations such as those worked in India and Ceylon was non-existent in the Shan States. In Tawngpeng, the average size of a tea garden was just over an acre in size.

[14] The Commissioner of the Federated Shan States, John Clague, noted that any villager could claim tea land in which he had cleared jungle and planted tea. Generally speaking, full rights to the crop were granted to the planter or occupier as long as State taxes had been paid.

[15] Custom dictated that tea gardens could be transferred only through sale or inheritance to another member of the same village; however, by 1911-12, in the vicinity of Namhsan, some purchasers and inheritors of tea gardens were not residents of the villages concerned.

[16] Moreover, the Tawngpeng Sawbwa used his own finances and an agricultural loan from the State treasury to obtain large holdings and bring the purchased land under tea cultivation in the early twentieth century.

[17] By the 1930s, the communal aspect of the tea gardens was maintained through the village possessing the right to approve or deny an outsider’s bid to obtain land in any particular village.

[18] On average, a worker is able to gather a vie of tea leaves per day.

[19] For this type of labor over a season, a tea-pluckers in 1921-22, would earn Rs.10-12 if the wages were paid three or four months in advance. The more patient laborer, who could afford to wait until the end of the season, received Rs. 20-22. Workers engaged in weeding or hoeing gardens earned the same wages as pluckers. Alternatively, a worker might decide to keep one day’s work in the plucking season provided that three day’s work was done in the garden at a later date.

[20] At Zeyan village, which was reputed to produce the highest quality and quantity of tea in Tawngpeng, Chinese buyers from Mandalay paid the following prices for wet tea: Shwepyi Ñ Rs. 25 per 100 vises, and for Hka-gyin and Hka-rawt Ñ Rs. 20 per 100 vises. Dry tea sold at the following rates: Shwepyi Ñ Re. 1 per vises, Hka-gyin Ñ 12 annas per vises, Hka-rawt Ñ 8 annas per viss, and Hka-reng Ñ 4 annas per vises. Once the tea reached Mandalay, wet tea obtained Rs. 40-60 per viss, and dry tea fetched Rs. 150-200 per 100 vises. In 1895-96, approximately 15,000 bullock-loads of wet tea were sold, and about 25,450 vises of dry tea were produced including 10,000 vises for local consumption. The remaining dry tea was sold or bartered to traders in exchange for cash or ngapi (fish-sauce), dried fish and rice. The State imposed a tax of Re. 1-0-2 to Rs. 2 on pickled tea sent to Mandalay, and a tax of Re. 1-8-0 to other destinations. In addition, tea transported by pony faced a tax of Re. 1-4-0. Dry tea shipped by bullock-cart was taxed at a rate of Rs. 2 per load while dry tea carried by coolies was assessed at Re. 1 per vises.

[21] Responsibility for collecting the various taxes was delegated to village headmen who often appointed agents to gather the revenue.

[22] Mr. R.C. Wright, a tea-planter from Ceylon, offered an assessment of tea production in Tawngpeng: It is good Manipuri jat, dark leaf…. Some of the bushes are good, but as a rule are cut and hacked about and spoiled for tea-bearing purposes. It is all one jat, Manipuri, which is the wild tea of Burma. From what I could see, if it were properly cultivated, it would be very good tea and of very fine quality.

[23] Moreover, a future Viceroy of India, George Curzon, visited the Shan States in 1893 and indicated that the tea industry held potential for developing an export trade.

[24] But, a lack of investment capital combined with a poor transportation network meant that a tea industry geared to an overseas market was absent in Tawngpeng. In regard to transportation, Table 1 demonstrates that mules, bullocks and coolies carried more loads of tea to the railway head at Kyaukme in the 1920s than did Lorries. Nevertheless, the domestic tea industry was indeed substantial. Tea provided Tawngpeng with a cash crop that could be exported to Burma proper.

[25] Based upon figures of carriage provided by the Burma Railways, Clague pointed out that, ‘in terms of Shan dry tea at least 11 million pounds are exported from Hsipaw and Tawngpeng every year’. The corresponding figures for wet tea equaled 13,633,669 pounds in 1934.

[26] R. McGuire of the Government of Burma’s Reconstruction Department reported, in 1944, that the total amount of tea consumed in Burma annually before the Japanese invasion was 16,500,000 pounds of which 14 million pounds originated in the Shan States.

[27] Clearly, the Shan tea industry had been successfully adapted to consumer demand in Burma proper. But the depression of the 1930s created a crisis in which tea prices and sales fell with a consequent hardship for cultivators. One solution devised to overcome the slump in the domestic market was to export tea from the Shan States overseas. However, the proponents of the plan ran into difficulties over misunderstandings and legal undertakings by the tea-licensing authorities in India. Sympathetic officials in London were powerless to intervene in defence of the Shan tea industry so long as Burma remained a province of British India. It was not until Burma had been separated from India that the Government of Burma could contemplate granting approval to the export of tea from the Shan States overseas. By 1941, the Shan tea industry had some prospects of developing a small overseas trade in high-quality tea to supplement the domestic industry. The slump in the Shan tea industry was noticeable in 1931-32. Shwepyi had fallen in price from a rupee in April and May to 6-8 annas a vise in later months. Furthermore, the revenue acquired from the tax placed upon Shan tea exported to Burma proper dropped from Rs. 113,805 to Rs. 79,882.

[28] During 1932-33, Shwepyi produced in Tawngpeng improved in price from a low of 8 annas to a high of Rs. 1-4-0 per vise; however, this gain was offset by an estimated 50 per cent decrease in production that resulted from a dry spell in February, Table 1. Transport of Tea from Tawngpeng State to Kyaukme WET TEA DRY TEA Motor Motor Man Year Lorries Carts Bullocks Lorries Carts Mules Bullocks Loads 1925-26 11 42 42,377 4 246 13,912 926 10,587 1926-27 379 41,407 54 380 34,360 2,255 1927-28 6 392 40,954 64 387 34,611 2,367 1928-29 108 397 37,608 242 290 15,363 2,995 3,792 1929-30 187 589 35,992 383 198 11,757 2,998 3,347 Source: Brief Review of the Working of Federation in the Shan States, 1 922 to 1931 (Rangoon: Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma, 1931), P. 39 March and April.

[29] A lack of rain continued to hamper production in the following year.

[30] In addition, as Table 2 demonstrates, the prices paid for tea to cultivators fell steadily. Table 2. Prices Paid to Cultivators in the Shan States for Tea per 100 vises, 1929-1936* Price Paid Year (Rs.) 1929-30 125 1930-31 1122 1931-32 100 1932-33 65-70 1933-34 60-70 1934-35 40-50 1935-36 35-40 [Source: IOR: M/3/512. Secretary, Government of Burma, Revenue Dept., Commerce and Minerals Branch to Secretary, Government of India, Dept. of Commerce, No. 49K36(244), 23 April 1936.] What could be done to improve the situation? The answer laid in the potential for growth which Wright, the tea-planter from Ceylon, and Curzon, the future Viceroy, had envisioned in the late nineteenth century. The opportunity to act upon this potential arose with the arrival of E.H. Beadnell to the Shan States. He was a private investor who had experience with tea production in India and had financial connections in London, which would be crucial in raising the capital necessary to develop the tea industry in the Shan States. As a result, Hkun Pan Sing, the Tawngpeng Sawbwa, and Saw On Kya, the Hsipaw Sawbwa, backed by Beadnell’s expertise, made an application in Jan 1934 to the Tea Licensing Committee in New Delhi to grant Beadnell an export license for one million pounds of tea for sale within the Empire.

[31] The Sawbwas believed that with Beadnell’s support the domestic tea industry in Tawngpeng, Hsipaw and Mongmit could be transformed into an Empire export-oriented industry that would be capable of counteracting the undesirable consequences of the slump through economic growth. Unfortunately for the proponents of the plan, the Tea Licensing Committee rejected the request made by Hkun Pan Sing and Sao On Kya, ‘on the grounds that those States [Tawngpeng and Hsipaw] do not form a part of British India’.

[32] Obviously the criterion employed by the Tea Licensing Committee to reject the application for an export quota in Shan tea was incorrect. The Shan States became part of British India in 1886. However, the Committee did have a legitimate concern over the need to restrict any extension of land under tea production for export. Profits to tea producers were in a depressed state since the onset of the worldwide economic slump. The weakened world market for tea was compounded by the fact that in 1929 tea supply had exceeded consumption by 58 million pounds.

[33] Overproduction of tea within the British Empire and the large quantities of cheap tea that had entered the London market from outside the Empire had served to create a huge stockpile in tea and a reduction in profits.

[34] The tea surplus crisis intensified in 1932 when India produced a bumper crop of tea at a time in which prospects for increased consumption were unfavorable. To counter the problems in the tea industry, the major tea exporting countries (India, Ceylon and the Dutch East Indies) began discussions in 1931 to regulate production and obtain a balance between supply and demand.

[35] The Colonial Office desired that the tea market be permitted to stabilize itself without any international co-operation. It was thought that the tea industry of the Dutch East Indies would be the first to collapse and thus rid the Empire industry of a competitor.

[36] However, it was clear that a number of British companies in India and Ceylon would also collapse or be forced to suspend dividend payments; therefore the Secretary of State approved the scheme.

[37] Negotiations went forward and culminated in the International Tea Agreement of 1933, which limited tea exports from the three countries to 85 per cent of their average exports in the best exporting year between 1929 and 1931. For example, under this formula the export quota allotted to Ceylon was 215,522,617 pounds of tea.

[38] Henceforth, until the expiration of the Agreement in 1938, exports of tea from India, Ceylon and the Dutch East Indies would be regulated to meet consumer demand and to limit any extension of land under tea cultivation. Sir Percival Griffiths noted that, ‘an International Tea Committee was set up to co-ordinate all this action and in India the Tea Control Act to give effect to the agreement was passed in 1933′.

[39] Thus, a quota system was introduced to regulate the export of tea from British India. It was a request by the Sawbwas on behalf of their agent, Beadnell, to obtain a quota license for export, which was rejected by the Tea Licensing Committee. The time was not yet ripe for an expansion of the Shan tea industry into Empire markets. Not surprisingly the decision of the Tea Licensing Committee created a bitter and hostile response in Tawngpeng. In a letter written to Beadnell, Hkun Pan Sing queried, ‘Will the TLC be dreaming up further Rules to shut out the Shan States’?

[40] In 1934-35, the Shwepyi tea crop faced another setback, which led to a drop in the amount of taxes paid from tea and thathameda to the State treasury.

[41] The Sawbwa had felt that he was on solid ground in attempting to promote the export of Shan tea within the Empire, which would help to alleviate the gloomy economic situation. The State already had a tea industry that seemed capable of expansion. In addition, Tawngpeng had two tea experts who had received their training in Ceylon. The Chief Minister, Hkun Hkam Heng, had gone to Peradeniya, Ceylon in 1924 to study tea production. He received the post of Tea Expert upon his return to Tawngpeng in 1925, a position which he held until he became Chief Minister in 1932. His replacement as Tea Expert, Hkun Tun, had also gone to Ceylon in 1924 to study up-to-date methods of tea cultivation and manufacture.

[42] The Sawbwa sent another emotional missive to Beadnell in August 1935: Sir Joseph Bhore being an Indian certainly has no interest in Burma or the Shan States. He will do his best to instill the idea to Government not to give any privilege which is to be beneficent to Burma or the Shan States, but the British Government ought to realize that Burma or Shan States are part of British Empire and His Majesty’s subjects should get equal treatment. Why should British Government treat us differently Ñ are we not British subjects? If we are not given the same privilege as Indians, then I should say that we are not regarded as His Majesty’s subjects and it would be wrong for the British Government to treat us differently. Our people are dependent upon the only product of tea and if we are not given this privilege of having a quota, it would only mean that the Government does not care 3 whether its subjects are starved or not.

[43] In his letter, the Sawbwa seemed to be questioning the utility of remaining within the British Empire. Notwithstanding the depressed state of the world economy, and the emotional outpourings of the Tawngpeng Sawbwa, the inability to acquire an export quota for Shan tea demonstrates the vulnerability of interests put forth by a seemingly isolated voice on the periphery of Empire. Officials in both Burma and Britain did materialize in support of the Shan tea industry. Clague, for one, recommended the scheme to Rangoon. He suggested that a guaranteed quota for Shan tea would help to alleviate the financial crisis faced by tea growers. In his outline of the situation, Clague wrote, The tea gardens have been exceedingly hard hit by the great depression in prices in Burma, which is their sole market at present. At one time during the depression tea was almost unsaleable, and in the Tawngpeng State, in particular, barter for rice had taken the place of many transactions.

[44] But, little could be done in view of the International Tea Agreement. Beadnell contacted his brother-in-law in Britain, Colonel Swainson, in an effort to tap parliamentary aid.

[45] Swainson gained a sympathetic ear from the Labour Member of Parliament for Limehouse, Clement R. Attlee. Attlee addressed two letters to the Secretary of State for India in defence of the Shan tea industry. In the first letter, Attlee pointed out that, ‘it looks as if the interests of a small local industry in Burma was being deliberately damaged in the interests of the big Indian industry’.

[46] In his second letter to Hoare, the deputy-leader of the Parliamentary Labor Party noted that the Indian Tea Committee did not realize that the Shan States were part of British India; moreover, he wanted, ‘…to know whether the Government of Burma took any steps to protect their interest’.

[47] Both Clague and Attlee stressed the importance of tea to the local economy in their appeals. Another determined, and more vocal, ally of the Shan cause entered the debate in the person of R.H. Craddock who had been the Lieutenant-Governor of Burma from 1918-23. Craddock had been the architect of the Shan States Federation in 1922, and he did not want the Shan tea issue to be neglected. The Sawbwa’s letter to Beadnell was of particular significance to Craddock: …It deserves attention because it is the genuine outpouring of a Shan Chief to his Agent…. it is most important that the Chiefs should not be under the impression that they are of no account in the British Empire. In the event of any troubles arising in Burma proper…it is very important that the Shan Chiefs and their people should be well affected to the British Empire. They are the buffers between China and Burma.

[48] The former Lieutenant Governor had more to say than to outline the essence of the political and strategic roles that the Shan States were expected to play in the Empire. He attacked the Governor of Burma, Sir Hugh Stephenson, for his disappointing performance in not undertaking a more vigorous defence of the local Shan interest. He argued that a duty of the Governor was to promote issues important to, ‘the ignorant Palaung’ and, ‘to see that the Shan Chiefs are equitably treated’. The Governor had failed in his duty according to Craddock: ‘…I have great respect for Sir Hugh Stephenson but I cannot honestly feel that he has realized that the whole question turned upon him….’. Finally, Craddock urged Lord Zetland, who had replaced Hoare as Secretary of State for India, ‘to make it clear that it is the Governor-General and not the Tea Committee who is the proper authority to put matters right’.

[49] The rather brusque handling of the affair by the Tea Licensing Committee had generated a reaction, which demanded a more detailed and delicate study of the matter. Whether or not the more forceful approach advocated by Craddock would have succeeded with the Tea Licensing Committee is open to debate, but it is possible that the Committee would have handled the issue with more tact and knowledge than was displayed in their response of 14 February 1934. The key difficulty in finding a solution to the Shan tea issue was that virtually nothing could be done whilst Burma remained a province of India. One area in which there was some room to maneuver centered upon the Indian Tea Cess Act. In 1901, the Indian Tea Association made a proposal to the Government that a cess should be imposed upon tea exported from India. The revenue obtained from the cess could be used to promote the consumption of Indian tea in the domestic and world markets. Ceylon had already provided a lead in this regard. In 1892, Ceylon had imposed an export duty upon tea, which, by the turn of the century, brought approximately Rs. 3 lakhs per annum for the Ceylon tea publicity campaign. The Indian Government accepted the proposal, and legislation for a Tea Cess became law on 1 April 1903. A committee of 20 members was established to administer the cess from representatives appointed by the Bengal and Madras Chambers of Commerce, the Indian Tea Association, and by the Viceroy. As of April 1935, the cess on exports of Indian tea stood at 12 annas per 100 pounds.

50] In what way did the Indian Tea Cess Committee bring benefits to the Shan tea industry? At the India Office, D.H. Monteath provided the answer: The papers in connection with Mr. Beadnell’s application suggest that the Government of India has hitherto had little, and the tea trade of continental India no knowledge of the production of tea in Burma. The report of the Indian Tea Cess Committee is devoid of any evidence of knowledge of, or interest in the Burma side of tea production. It may be inferred that Burma tea growers, such as they are, derive and have derived no benefits from the activities financed by the Tea Cess, and this inference is strengthened by the fact that the Tea Cess Committee does not contain and has not contained a representative of Burma.

[51] In other words, the Shan tea industry had yet to reap any benefits from Burma’s inclusion within the scope of the Tea Cess Act. Consequently, almost two years after the controversy had begun, Monteath recommended that the Indian Tea Cess Act should be so amended that it would cease to apply to Burma. In addition, he wanted the amendment to become effective prior to the separation of Burma from India.

[52] Monteath pointed out that the exclusion of Burma from the provisions of the Act would be advantageous for both India and Burma. India would be able to assess the cess upon tea exported to Burma, but continue to receive, ‘…the not inconsiderable exports of Burma tea to continental India…free of this cess’. On the other hand, the increased cost of Indian tea might persuade consumers in Burma to purchase domestic tea, which would stimulate growth in the local industry. Furthermore, tea exported from Burma could prove to be an attractive buy for overseas customers since it would be cheaper than tea exported with the cess applied. Most importantly, Monteath stressed the point that India and Burma would remove, ‘…an anomaly which might, in time, become an irritant’.

[53] Neither the Indian Tea Licensing Committee nor the Commerce Department of the Indian Government expressed any sympathy or agreement with the statements in support of the Shan tea industry. The Committee’s Secretary was emphatic that only the individual tea garden owners, and not the Sawbwas of Tawngpeng and Hsipaw, were legally entitled to apply for export quotas on behalf of Beadnell: Forms purporting to be applications for quota have been received from Mr. Beadnell in respect of the States not in respect of the individual tea gardens in the States…. the Sawbwas of the States…. are not the owners of the estates and it is only the owners who are recognized by the Licensing Committee in their administration of the Act.

[54] The Act was designed to deal with large plantation owners in the first instance, and small garden owners if necessary, but a provision to negotiate with traditional leaders who attempted to act on behalf of their subjects did not exist. Of course, to permit the Shan States to export tea would be, ‘a violation of the international obligations undertaken by the Government of India on behalf of India and Burma’.

[55] This point was the key according to the Government of India. As the Viceroy pointed out to Zetland: ‘We do not feel justified in taking action to remove any of the technical difficulties which stand in the way of the allotment of a quota to the Shan States, since their object is to defeat the purposes of the Act’.

[56] H. Dow, acting on behalf of the Commerce Department in India also took issue with certain allegations made by critics such as Craddock and Monteath. He refuted allegations that the slump in the Shan tea industry could be associated with the Indian policy of tea control. While he conceded the point that Indian tea had entered the domestic market of Burma in 1934 at progressively reduced prices,

[57] he argued, ‘that 1934 was the year in which prices reached their maximum depression and in which the purchasing power in Burma was at its lowest ebb’. Also, he corrected Monteath’s premise that India received large quantities of tea from Burma. Dow doubted that little, if any, Burma tea reached India or anywhere else. In fact, the Burma tea exports mentioned by Monteath actually consisted of Chinese tea, which was shipped to Tibet via Burma and Calcutta. Dow concluded, ‘that the Indian Tea Control Act does not apply to those States [Tawngpeng and Hsipaw]‘, and that he would not recommend the extension of the Act to those States.

[58] The Shan tea issue was brought into the Legislative debates in India and Burma during the fall of 1936 but without success.[59] In London, Dow’s letter created an atmosphere of resignation and frustration. Zetland continued to believe that it was a technical decision,

[60] Whereas in the House of Commons R.A. Butler stressed India’s position as one of expediency.

[61] An official at the India Office realized that Burma’s hands were tied until the International Tea Agreement expired in March 1938.

[62] Monteath suggested that the issue was reminiscent of a scene from the pen of Lewis Carroll: The position of the Shan seems rather Alice-in-Wonderland-like: the Tea Control Act has never been applied in the Shan States, so they can have no quota: but as soon as their tea comes into the ports of Burma where the Act is in force it becomes subject to it to the extent that it cannot be exported without a license; & no license can be given because it is not within the quota which cannot apply. Monteath added that he had been advised that the tea produced in the Shan States was similar to, ‘high-grade China tea’. But, the possibility of India ever acting to promote the Shan tea industry seemed out of the question, thus he believed that Beadnell’s only recourse would be to bypass the tea restrictions imposed from India altogether by exporting Shan tea ‘ad-lib’ through Bangkok, Siam.

[63] Craddock knew that Burma would be unable to act independently from India until the Agreement between India, Ceylon and the Dutch East Indies lapsed in 1938. However, he did not believe that India’s ability to win debating points had diminished the crisis of low tea prices for growers or for the Sawbwas. He adopted a pragmatic, but political stance: ‘It is politically unwise to allow this grievance to simmer among some important Shan States a day longer than is necessary’.

[64] Craddock’s concern centered upon the discontent, which might be generated among the Sawbwas of the tea-growing States who felt that the government had done little to advance their interests. The Indian Government did make one concession to the India Office. Monteath’s recommendation to exclude Burma from the operation of the Tea Cess Act before separation was accepted. The official notification to indicate that Burmese seaports ceased to participate in the levying of an export tax upon tea was issued 17 February 1937.

[65] The reasons behind this decision were explained by Zafrullah Khan. One, little revenue would be likely to accrue from Shan tea exports. Two, Burma did not have a representative on the India Tea Market Expansion Board. Three, Burma’s exclusion before separation would prevent acrimonious wrangling in the future between India and Burma over the handling of the Shan tea issue.

[66] Clague wrote that at the time when India had joined with Ceylon and the Dutch East Indies to control and restrict tea exports the Shan tea industry had not been considered since, ‘there were no proposals…for manufacture of European tea in the Shan States’.

[67] The door had now been opened for the Shan States to prepare and promote a worldwide export market in tea. The consensus at the Burma Office was that separated Burma would not join with India, Ceylon and the Dutch East Indies in ratifying a renewed tea restriction agreement in 1938. Indeed, this prediction proved to be accurate. After separation, the Government of Burma informed India that it could not become a participant since the tea regulating countries would be unlikely to approve the development of an export industry in Shan tea, nor would the legal definition of an ‘estate’ be applicable to the Palaung and Shan tea gardens. And yet Burma did seek to gain an advantage within the restriction scheme. The Government wanted to continue to import tea from the regulating countries at 4-5 annas per pound while at the same time export Shan tea at just over 10 annas per pound.

[68] But no, the Government of India was not prepared to accede to a request of that nature, and the separated Government of Burma decided to remain outside the renewed International Tea Regulation Scheme of 1938.

[69] One Burma Office official speculated that Burma’s refusal to join the tea regulation agreement might lead to a 150 per cent increase in price for imported tea, and that any attempt to obtain tea seeds from abroad would fail.

[70] Clague was more optimistic. He commented, ‘India treated Burma badly over the proposals…for a quota for Shan States’ tea’. He forecast that any large increase in the price of imported tea would only serve to stimulate tea production in the Shan States as a cheaper source of supply. Moreover, he thought that the opium problem might be solved by substituting tea for opium as a cash crop east of the Salween River.

[71] Craddock had warned of dire consequences if the Sawbwas held the Burma Government to have been negligent in protecting their interests and those of their subjects. Clague indicated that it had been concern for the welfare of the tea cultivators that had spurred the Sawbwas on to press for an export quota in tea.

[72] Although there may be a case that can be made in favor of the argument that the Sawbwas were genuinely worried about the economic plight of the tea growers, the subsequent action of the Tawngpeng Sawbwa suggests that another, less generous, argument might have been more important. To illustrate, Hkun Pan Sing dismissed Beadnell from the post of Tea Agent and appointed his assistant, Mr. Bennett, as his replacement. Bennett and the Tawngpeng Sawbwa lobbied the Government of Burma to approve their application to India for an export quota in Tawngpeng tea, but they had no intention of fulfilling the terms of the export quota if their application was successful.

[73] The conspirators planned to sell their quota to Mr. Ramchand Daga of Messrs. Kaniyalal Laxminarain of Calcutta and keep the money from the sale of the quota for themselves without exporting one ounce of Tawngpeng tea.

[74] Stephenson observed that, ‘It was pure graft…. which could not have benefited the Shan States though it might have put some money into the Sawbwa’s pocket’. The scheme collapsed when the Government of Burma refused to sanction the application for a quota export.

[75] Needless to say, the incident deprived the Tawngpeng Sawbwa of any right to be morally outraged at the policy of the Government of Burma. A ramp along the lines described above did not prove to be unusual under the conditions of control and restriction in India. Griffiths reports that the selling of quotas was one of the flaws in the regulatory system. He discovered that many small tea estates were able to obtain quotas, which were then sold to middlemen without any tea leaving the estate. Other estate owners sold their quota and kept the tea produced for sale in the domestic market.

[76] Thus, for some tea estate owners and less than honest merchants, the tea restriction system turned out to be a financial bonanza which required little effort beyond that of obtaining the export quota license. Beadnell had proved to be an honest man who displayed confidence that he could obtain the consent and labor of the Palaung and Shan tea growers to transform the domestic tea industry into one capable of gaining a share of the world market. Clague believed that Beadnell had a fair chance for success.

[77] Nothing like this could be said for the quota fraud that Hkun Pan Sing and Bennett had planned. Furthermore, the incident served to vindicate the cautionary approach of the Burma Government somewhat in light of Craddock’s criticism. A large-scale export industry in Shan tea could not be created overnight once the Tea Restriction Agreement ceased to apply to Burma. Moreover, Burma proper suffered from an economic downturn in the summer of 1938 largely as a result of ethnic tension between Indian Muslims and indigenous Buddhists caused by the re-publication of a book written by Shwe Hpi, an Indian Muslim, which had less than kind remarks to make about the Buddhist religion.

[78] Nevertheless, the Lipton Company purchased a large quantity of Tawngpeng tea to test its marketability in Burma proper.

[79] And the Bombay Burma Trading Corporation Limited took some steps towards indicating the potential for Shan tea exports outside Burma. In February 1939, the Corporation erected a factory to manufacture tea at Namhsan, the capital of Tawngpeng State. During its first season of operation, which lasted from 1 Aug. to 8 Nov. 1939, 47,900 pounds of tea were produced of which 16,732 went to Burma proper, Australia imported 10,812 pounds, and 4,128 pounds were sold at the Colombo Auction in Ceylon.

[80] This modest, but encouraging, start was surpassed in the second season of production, which began 6 April and ended at the end of June 1940. The Namhsan factory produced 154,561 pounds of tea of which 63,940 pounds were sold in Burma proper, 11,772 pounds were auctioned in Ceylon, and the United Kingdom Ministry of Food purchased 29,414 pounds.

[81] Collis noted that in Tawngpeng, They exported fifteen million pounds annually. We were continually meeting tea caravans; the tea packed in tall, white baskets with leaves at the top, which were carried generally by bullock, a basket on each side of the saddle.

[82]Although the 1939/40 Tawngpeng State budget did not reflect the upturn in its tea economy, this situation can be explained by the generous contribution made by the Tawngpeng Sawbwa to the Lord Mayor’s Fund for War Relief of Rs. 1.33 lakhs.

[83] Tea growers had reason to be satisfied as well. Not only did they have new markets for their tea, but also the company guaranteed the tea suppliers approximately ‘Rs. 100 per 100 vises of dry tea’ irrespective of fluctuations in the market.

[84] Obviously, tea produced in the Shan States was not about to displace or challenge the share of the market held by the major tea-producing countries such as India and Ceylon. For example, Ceylon exported 235,739,000 pounds of tea in 1938.

[85] And yet the Tawngpeng tea growers had demonstrated a potential for growth by obtaining a share of Empire tea sales, which brought benefits to investors, cultivators and consumers alike. Unfortunately for the fledgling Shan export industry in tea, its full potential was never realized. The Japanese occupation of Burma put an end to the progress attained in 1939 and 1940. Subsequently, the Shan tea industry reverted to a purely domestic affair after Britain transferred power to an independent Burma in 1948.

[86] Never again would Shan tea have commercial success in the international market.

Notes

[1] Lieberman, V. 1991. “Secular Trends in Burmese Economic History, c. 1350-1830, and their Implications for State Formation”, Modern Asian Studies 25(1):9

[2] Tawngpeng, or Taungpeng, is an English corruption of the Burmese name for the State, Taung-Baing. Loi Long is the Shan name, which means big hills. The equivalent in Thai is, Doi (hill) Luang (big). The Chinese refer to Tawngpeng State as, Ta Shan (big hills) or Ch’a Shan (tea hills). Scott, J.G. and J.P. Hardiman. 1901. Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States (hereafter referred to as GUBSS) II:III: 250

[3] This king is also known as Aloncansu. The earliest-known Burman kingdom was centred at Pagan although in its initial stages it tended to be dominated by Mon and Pyu notions of art, architecture, religion and administration. The initial Burman identity can be associated with the reign of Alaungsithu. In the historiography of Burma, controversy has centred upon the reign of this king. According to G.H. Luce, Ceylon led a successful attack against Pagan in 1165 to unseat Alaungsithu. However, a later article by Michael Aung-Thwin demonstrates that Pagan did not come under attack from Ceylon at this time. Luce, G.H. 1970. “Aspects of Pagan History – Later Period”, in Tej Bunnag, and Michael Smithies (eds) In Memoriam Phra Anuman Rajadhon. Bangkok: The Siam Society, pp. 129-146. Aung-Thwin, M. 1976. “The Problem of Ceylonese-Burmese Relations in the 12th Century and the Question of an Interregnum in Pagan: 1165-1174 A.D.”. Journal of the Siam Society 64(1):53-74

[4] Taungthu cultivators practise shifting agriculture.

[5] GUBSS II:III: 252

[6] The British grouped the main block of the Shan States into a federation as of 1 Oct. 1922.

[7] Shan States and Karenni. List of Chiefs and Leading Families (Corrected up to 1939). Simla: Government of India Press, 1943:62; India Office Library and Records (IOR): V/27/70/57.

[8] Collis, M. 1938. Lords of the Sunset. A Tour in the Shan States. London: Faber and Faber Limited, p. 213

[9] GUBSS II:III:254-255. The Shan States of Hsipaw and Mong Mit also manufactured tea. In 1930, Tawngpeng obtained Rs. 206,619 from tea out of a total of Rs. 920,568 in revenue. Hsipaw gained Rs. 130,900 from tea from Rs. 1,103,243 in total revenue. Mong Mit acquired Rs. 229,793 in total revenue of which Rs. 8,800 came from tea. Rangoon Superintendent. 1931. Brief Review of the Working of Federation in the Shan States, 1922 to 1931. Rangoon: Government Printing and Stationery, pp. 44-46. IOR: M/3/252

[10] Letpetso is the Burmese word for wet tea. In Shan, wet tea is known as neng yam.

[11] Dry tea is letpet chauk in Burmese.

[12] GUBSS I:II (1900), pp. 357-358; GUBSS II:III, pp. 256-257 [13] GUBSS I:II, p. 357

[14] John Clague, Commissioner, Federated Shan States to the Secretary, Revenue Dept. (Burma), No. 168/21-3, 5 July 1934. IOR: M/3/512

[15] In Tawngpeng State taxes consisted of thathameda and tea taxes. Thathameda is similar to a poll-tax.

[16] Office of the Superintendent. 1912. Report on the Administration of the Shan and Karenni States (hereafter referred to as RASKS) for the year 1911-12. Rangoon: Government Printing, Burma, p. 13. IOR: V/10/532

[17] Ibid., p. 14

[18] Clague to the Secretary, Revenue Dept. (Burma).

[19] GUBSS II:III, p. 257

[20] RASKS 1921-22, p. 18. IOR: V/10/533

[21] GUBSS II:III, p. 256. A viss is a Burmese unit of weight equal to 3.64 lbs.

[22] Ibid., pp. 255-256

[23] GUBSS I:II, p. 358

[24] Curzon was staying with Scott in Lashio. G.N. Curzon to Lord Carrington, 15 June 189(?). MSS. Eur. F 111/81A. The Curzon Collection.

[25] The Burman heartland, or Burma proper, comprised the central Irrawaddy plain, and is the area which was ruled by Burman sovereigns in the pre-colonial period from the mid-sixteenth century until 1853.

[26] Clague to the Secretary, Revenue Dept. (Burma).

[27] R.E. McGuire, Reconstruction Dept., Scheduled Areas Branch, Govt. of Burma, Simla to F.W.H. Smith, Burma Office, D.O. No. 2RD(PP)43 Part I, 5 Sept. 1944. IOR: M/3/1715.

[28] Report on the Federated Shan States (hereafter referred to as FSS) for the year 1931-32, p. 31. IOR: V/10/534

[29] FSS 1932-33, P. 30. IOR: V/10/535

[30] FSS 1933-34, P. 30. IOR: V/10/536 * The figures for prices paid represent the average prices during any given year and are not strictly accurate since “precise accuracy is made impossible by the different qualities put on the market in varying quantities and at fluctuating prices at successive periods of the year”.

[31] Saw On Kya, Sawbwa, Hsipaw State to Tea Restriction Committee, 20 Jan. 1934; Hkun Pan Sing, Sawbwa, Tawngpeng State to Tea Restriction Committee, 23 May 1934. IOR: M/3/512.

[32] Joint Controller, Indian Tea Licensing Committee, Calcutta to E.H. Beadnell, 14 Feb. 1934. IOR: M/37512

[33] Griffiths, Sir Perceval. 1967. The History of the Indian Tea Industry. London:Weidenfeld and Nicholson, p. 188

[34] Ibid., p. 315

[35] Antrobus, H.A. 1957. A History of the Assam Company 1839-1967. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable Ltd., p. 214

[36] Note by Clauson, a Colonial Office Official, 23 Nov. 1932. Public Records Office (PRO): CO 54/914/14

[37] Memorandum. Notes of a meeting on 15th Dec. 1932 with representatives of the Ceylon Association. PRO: CO 54/914/14 [38] Forrest, D.M. 1967. A Hundred Years of Ceylon Tea 1867-1967. London: Chatto & Windus, p. 231

[39] Griffiths, op. cit., p. 191

[40] Hkun Pan Sing to Beadnell, 27 June 1934. IOR: M/3/512

[41] FSS 1934-35, P. 4. IOR: V/10/537

[42] Shan States and Karenni, op. cit., p. 64

[43] Hkun Pan Sing to Beadnell, 18 Aug. 1935. IOR: M/3/512

[44] Clague to the Secretary, Revenue Dept. (Burma).

[45] Beadnell to Major C.R. Attlee, 11 Jan 1935. IOR: M/3/512

[46] Attlee to Samuel Hoare, 3 Jan. 1935. IOR: M/3/512

[47] Attlee to Hoare, 12 Jan. 1935. IOR: M/3/512

[48] R.H. Craddock to Lord Zetland, 16 Dec. 1935. IOR: M/3/512

[49] Ibid.

[50] The above discussion regarding the Indian Tea Cess is based upon, Griffiths, op. cit., pp. 596,598,613

[51] Extract from a letter, D. Monteath to Commerce Dept. (India), 7 Feb. 1936. IOR: M/1/195

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Secretary, Indian Tea Licensing Committee to the Secretary, Commerce Dept. (India), No. 886/S. 48-I. L.A., 18 March 1936. IOR: M/8/13

[55] H.S. Malik, Dep. Secretary, ‘Dept. of Commerce (India) to the Under Secretary of-State, India Office, Economic and Overseas Dept., 31 March 1937. IOR: M/3/512

[56] Lord Linlithgow to Zetland, 27 Aug. 1936. IOR: M/3/512

[57] Since 1930-31, approximately 3 million pounds of Indian tea had been exported to Burma annually. Dow to the Under Secretary of State, India, No. 224(I)-Tr(I.E.R.), 15 Oct. 1936. IOR: M/8/13. However, from 1936-39, an average of 4,606,748 pounds of Indian tea entered Burma at an average annual value of Rs. 21.02 lakhs. Report on the Trade and Customs Administration of Burma for the Official Year 1940-41. Rangoon. Government Printing & Stationery, 1941, p. 36. IOR: V/24/489.

[58] Dow to the Under Secretary of State, India, 15 Oct. 1936.

[59] Legislative Assembly Debates, 22 Sept. 1936, pp. 1614-1615; 12 Oct. 1936, pp. 24-30

[60] Zetland to Linlithgow, 27 July 1936. IOR: MSS. Eur. D 609/ 7. The Zetland Collection.

[61] Statement by R.A. Butler, House of Commons, 4 Dec. 1936. IOR: M/3/512

[62] Comment by E.J. Turner, Economic & Overseas Dept., India Office, 25 Nov. 1936. IOR: M/3/512

[63] Comment by Monteath, India Office, 28 Oct. 1936. IOR: M/3/512

[64] Craddock to Zetland, 12 Dec. 1936. IOR: M/3/512.

[65] Notification. Dept. of Commerce (India), 17 Feb. 1937.IOR: M/1/195

[66] Zafrullah Khan. Statement of Objects and Reasons, 17 Feb.1937. IOR: M/1/195.

[67] Clague, Adviser to the Secretary of State for Burma, Burma Office to M. Donaldson, Principal Secretary, Burma Office, 2 June 1937. IOR: M/3/512

[68] Comment by W. Johnston, Minute Paper B3787/38, Burma Office, 25 July 1938. IOR: M/3/108.

[69] The Government of Burma attempted to have Burma proper included within the scope of the tea agreement, but have the Shan States excluded. Government of Burma to Dept. of Commerce, India, 14 Feb. 1938. IOR: M/3/108.

[70] Comment by Johnston.

[71] Comment by Clague, Minute Paper B3787/38, 27 July 1938. IOR: M/3/108

[72] Clague to Donaldson.

[73] The Hsipaw Sawbwa did not join in this scheme. J.H. Wise, Revenue Dept. (Burma) to T.A. Stewart, Secretary, Dept. of Commerce, India, No. 245K35, 28 March 1936. IOR: M/3/512. For the dismissals of Beadnell by the Tawngpeng Sawbwa see, Hkun Pan Sing to Beadnell, 31 May 1936. IOR: M/3/512.

[74] Secretary, Indian Tea Licensing Committee to Stewart, No. 886/S.48-I.L.A., 18 March 1936. IOR: M/8/13; Note by Sir Hugh Stephenson, Adviser to the Secretary of State for Burma, Burma Office, 28 April 1937. IOR: M/3/512.

[75] Ibid. Stephenson had served as Burma’s Governor from 23 Dec. 1932 to 7 ;May 1936. [76] Griffiths, op. cit., pp. 191-192

[77] Clague to Donaldson.

[78] From 26 July until mid-Sept. 1938, 192 Indians died and 878 were injured during the communal strife. 171 people were injured through police action to restore order of whom 155 were Burmans. Cady, J. 1958. A History of Modern Burma Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, p. 324.

[79] FSS 1937-38, p. 39. IOR: M/3/226.

[80] FSS 1939-40, pp. 48,56. IOR: M/3/226.

[81] Ibid., p56.

[82] Collis, op. cit., p. 211.

[83] FSS 1939-40, P. 8; Hkun Pan Sing to the Secretary of State for Burma, 6 Sept. 1939. IOR: M/5/16. [84] FSS 1939-40, p. 56.

[85] Forrest, op. cit., p. 290.

[86] For example see, Report to the Pyithu Hluttaw. The Financial, Economic and Social Conditions of The Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma for 1985/86. 1985. Rangoon: Ministry of Planning and Finance.

Source: www.246.dk/teaburma.html

Background of The Palaung people in Thailand

The Palaung are the most recent ethnic group to arrive in Thailand. They have come here from neighboring Myanmar (Burma), where they are one of that country’s most ancient indigenous peoples. They have fled in the past 20 years from Shan State and Kachin State to escape persecution and oppression at the hands of Myanmar’s military rulers. Many of the Palaung in Thailand are refugees living in refugee camps.

The are three main sub-groups of the Palaung: Pale, Shwe and Rumai. Each of these sub-groups has their own language. Most of the Palaung who settled in northern Thailand are of the Pale, also known as Silver Palaung. The photographs here are of this sub-group. Their women are very distinct in their dress. This includes a bright red skirt, worn like a sarong. Typically in the past, these “tube skirts” were made from cotton, which the Pale grew and dyed themselves, and were hand woven. Nowadays the cloth is more commonly bought in markets and hand weaving is giving way to machines. Around their waist are worn quite heavy silver hoops. These are said to symbolize an animal trap, set by the Lisu people, which accidentally ensnared Roi Ngoen, a visiting angel from whom they believe they are descended. The hoops are also believed to afford protection to the women.